“To

be ignorant of what occurred before you were born is to remain always

a child. For what is the worth of human life, unless it is woven into

the life of our ancestors by the records of history?” ― Marcus Tullius Cicero

For my Children.

While many people focus on names and dates to fill a family

tree, the most interesting aspect of genealogy is learning about the

life and times of our ancestors. We can learn about American history

through our family’s history!

Some historical events are more popular than others – like the

signing of the Declaration of Independence, Women’s Suffrage or the

Apollo moon landing. But just as important are the historical events

that aren’t quite so popular – like

the Vietnam War, the January 6th.

Insurrection or the 1919

Chicago Race Riots. Exploring unpopular historical

events are just as instructive as the popular ones especially when

you learn about them through the context of an ancestor’s life.

My Great-Grandparents, Marek and Anna Niemiec, were early twentieth-century Polish immigrants

living in Chicago, Illinois. They immigrated

from Galicia, which is now in Southwestern Poland, and they were

ethically Polish.

Marek and Anna settled in one of the five Polish

neighborhoods in Chicago, the Lower West Side, in St. Casimir parish, or in Polish, Kazimierzowo.

One of the historical events they lived through was the 1919

Chicago Race Riots. I didn’t know about this history so I was

curious. What happened? Why? What

did Polish immigrants, like Marek experience during the riots …

what did they think about what was happening?

THE $10,000 question: Did

Marek participate in the

riots? Finally, what was the aftermath

of the riots, for Chicago … for Marek … for all

Americans?

WHAT HAPPENED? The 1919 Chicago Race Riots occurred between July 27 and August 3,

1919. Chicago was in the throes of a brutal heat wave. Thousands

flocked to the beaches lining Lake Michigan for some relief. Among

them was a group of Black boys that included 17-year-old Eugene

Williams. Eugene, who was on a raft, inadvertently drifted over the

invisible line that separated the Black and White sections of the

29th Street Beach. White boys and men began throwing rocks at the

Black kids hitting Eugene Williams knocking him unconscious, causing

him to slip off his raft and drown.

Police shrugged off requests from Blacks that the rock-throwing

men be arrested. After Eugene’s body was pulled from the water,

fighting ensued.

Soon, people – White and Black - on Chicago’s South Side,

were engaged in seven days of shootings, arson, and beatings that

resulted in the deaths of 38 people and 537 injured. The police

force, owing both to under staffing and the open sympathy of many

officers with the White rioters, was ineffective. Almost 1,000 Black

homes burned down or were bombed by rioters.

|

Rioters pulling an African American man from street car,then they beat him.

| |

|

Rioters stoning an African American man to death.

|

|

African American homes were bombed, a 6 year old child was killed in this bombing.

|

It was the long-delayed intervention of the Illinois National

Guard, and a rain storm, which finally brought the violence to a

halt. None of the White participants in the riot ever faced

consequences for their involvement.

Eugene Williams’ stoning

and drowning was the tipping

point. Before the

riots, tension had been building in Chicago basically due to three

socioeconomic factors.

First, there were the labor disputes.

Chicago steel workers and

stockyard workers had been on strike recently. Then, two weeks before the riot,

there was a

small labor walkout

at International Harvester – where

Marek was employed. Workers

wanted to organize into unions but management refused to even talk

with the workers. Following

the walkout by the small group

of International Harvester

workers, management sent a clear message about union organization - they shutdown

their factories for two

weeks putting 10,000

employees

out of work without pay for

two weeks.

The company blamed the workers and refused to negotiate with the

labor representatives as a

union

and would only speak with them through management

selected “works council.”

Union busting began even

before there were any unions! They called the union leaders “un-American” even when the company management was the only one with the power to shutdown.

Secondly, there

was social tension,

too. Soldiers

were returning home after serving in Europe during World War I. Black

soldiers, in particular, had experienced being treated as equal

citizens while they fought abroad. Returning to an America that

barely recognized their service and wanted them back in their

assigned, segregated places was not something they were willing to

accept.

|

... how African Americans were treated in their own country -the USA!

|

In addition, African

Americans were becoming economically successful They started banks,

real estate companies, and retail businesses. Their success was a

challenge to Chicagoans who held racist views and could only view

African Americans in the South, fulfilling a stereotypical

subservient role.

A popular film also added to

the social tension in our country. In

1915,

the film “Birth of a Nation” was released. President Wilson, who also

re-segregated the civil service, screened the film in the White House

and said, “It is

like writing history with lightning. And my only regret is that it is

all so terribly true.” - which

it most definitely is NOT!

The

film

is racist propaganda promoting

the

Klu Klux Klan. The

Klan did, and still does,

promote

militant

advocacy of white supremacy, antisemitism,

anti-Catholicism,

and anti-immigration.

|

Rioters running after African Americans with bricks in hand.

|

The

film and President Wilson’s response to it, contributed to the

nationwide acceptance

and revival

of the Klu Klux Klan contributing

to

the

social

tension in Chicago.

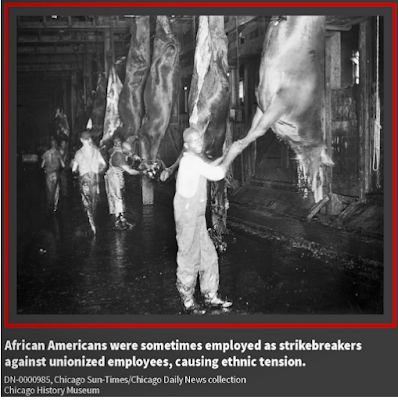

Finally,

adding

to the

social tension and labor

disputes

was the

fierce competition over jobs.

Between

1910 and 1920, the African

American population

in Chicago doubled from 50,000 to 100,000 due to the Great Migration.

African Americans migrated

north to Chicago

and

readily

accepted jobs in the city's slaughterhouses and factories

because the pay was better than what they'd received in the South.

Sometimes

African Americans were hired as strikebreakers and that

outraged some

European immigrants who'd traditionally held those jobs and who

wanted to unionize the companies they'd worked for. The

owners of the steel mills, stockyards, slaughterhouses and factories

held all the power. While the jobs were dirty and dangerous, they

were the difference between basic subsistence and homelessness. There were no social welfare programs in 1919, a job could mean the difference between

life and death.

These

were the socioeconomic times Chicago citizens, including Marek were

experiencing in July 1919.

Marek, age 38, and Anna, age 34, were living with their 5

children in a multi-family flat at 2926 W 25th Place in

southwest Chicago. Marek

and Anna’s neighborhood was on

the periphery of the riots.

The vast majority of

the shootings, arson and beatings took place in the “Black

Belt” neighborhood and near

the stockyards, some distance from their neighborhood. However,

there was some rioting just outside of Mareks' workplace, International Harvester. It is possible that he

witnessed some of the violence. An

African American was attacked and injured not far from International Harvester, where

Marek was employed.

Like all industrial workers, whether American citizens,

immigrants, or African Americans, Marek struggled to maintain a

steady, stable income. Since 1910 Marek worked at the International

Harvester factory located at Blue Island and Western Avenues. He was

an unskilled laborer working as a molder in the foundry.

|

Marek's (Mark) World War I Draft Registration Card

|

Even though he had a job, the Census records that Marek had

been "out of work" for 8 weeks in 1910 and he – indeed all industrial

workers - probably experienced company shutdowns, without notice and without pay, throughout the

years. In 1919 there was no job security, no way to negotiate

grievances nor unemployment benefits during company initiated

shutdowns. Marek certainly shared the same economic

pressures as did other Chicago workers. Between July 15 and 28, 1919, International Harvester shutdown, leaving Marek, once again, without pay. The riots began on July 27.

What did Polish immigrants, like

Marek, think about what was happening?

According to the 1920 United States Census,Marek could speak English but he could speak, read and write the Polish

language. Unfortunately Marek did not leave a personal

journal but, because he was literate in Polish, he

probably read the Chicago Polish language newspaper, Dziennik

Chicagoski,

which gives us insight

into the way Chicago’s Polish immigrants were thinking.

In the days before

television and social media, many people, like Marek would

read and discuss the daily newspaper with co-workers, family and

friends. On

the July 31, 1919 front page of the Dziennik

Chicagoski, Marek would have seen this political cartoon depicting

the City of Chicago crying over her history book.

Translation:

Title = “Two dark pages in the city’s history.

Text in book: “Race

Riots – Strikes”

“Strikes” refers to

industrial strikes

in general but also to the strike

by 15,000 street car and elevated train workers which paralyzed the

city – in the middle of the race riots!

Obviously, the image reflects the city’s

terrible situation and

the sorrow caused by

these two historical events.

Polish immigrants were also well informed about world events.

They were most interested in what was happening in Europe as a result

of the Great War and the break up of the Austria-Hungry and Ottoman

Empires. Dziennik

Chicagoski provided

coverage of the Russian Civil War, the Polish-Ukranian Border War,

and the Greco-Turkish War. But the newspaper also informed Chicago’s

Polish immigrants about the Mexican Revolution.

|

Galicia during the Polish-Ukranian Border War, 1919

|

Chicago “crying”

was published after two days of rioting. The

political cartoon below was

published on the front

page a few days later

on August 2, 1919. This one illustrates

how sorrow turned to sarcasm and also reflects the world view of

Polish immigrants in Chicago.

Title = “How Civilized!”

Bottom left: Black

man holding a switchblade, “Pogrom”;

White man holding a gun, “Racial”

Top, left to right:

Ukrainian - (laughing)

*Ukraine was in the midst of a Civil and Border War with Poland, and tens of thousands of Jews were

murdered in pogroms.

Cannibal -“How civilized!”

Bolshevik - “And this is Democratic

America!”

*Bolsheviks

were Russian Communists.

Turk - (laughing) “So free!”

*Turkey was fighting Greece for independence.

Mexican

- “How clever!”

*Mexico

was fighting a civil

war during which lands were taken, homes burned and innocent civilians were killed.

|

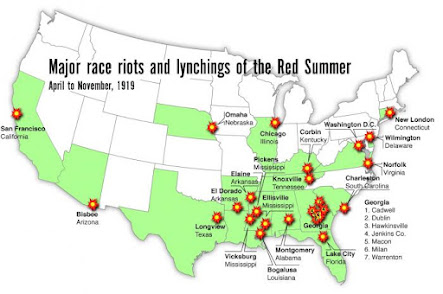

American Pogroms, 1919

|

Reading these

political cartoons and other news articles in the Dziennik

Chicagoski, Marek

may have thought he was still in Poland! However,

the United States was experiencing its

own version

of civil war and pogroms.

Perhaps he realized

that the United States is not exceptional but, unfortunately, rather

like every other country around the world.

|

Polish victims of a pogrom.

|

As a Polish immigrant from Galicia, Marek was already familiar

with another form of racism, antisemitism. Two years before Marek

immigrated to the United States, antisemitic literature circulated

widely in Galicia. A former priest, Stanisław Stojałowski, who was

attempting to create a peasant movement in Galicia, used antisemitic

slogans as political propaganda. Antisemitism soon became a staple of

European political campaigns. This led to the outbreak of violent

incidents – pogroms - against Jews in western Galicia, during which

people were injured and massive damage was inflicted on Jewish

property.

|

Chicago rioters celebrating the destruction and looting of an African American's home.

|

Many Polish immigrants fled their homeland due to these pogroms

and worsening socioeconomic conditions. Most Polish immigrants in

Chicago viewed the Chicago race riots within the context of their

experiences in Galicia. They viewed the race riots as pogroms.

They were not something to celebrate!

|

Ragen's Colts (Irish Gang)

|

Polish immigrants had a negative opinion of pogroms and did not want

to participate in the race riots. And, because they were immigrant

Catholics, obviously the Klan was not about to recruit them into the

racial violence. However, there was another group that played a

central role in violent attacks on African Americans in Chicago - Ragen's Colts.

Three years after the riots, a grand jury was convened. That grand

jury found that an Irish gang, Ragen's Colts, played a central role

in attempting to extend the bloodshed. Because Ragen's Colts were

Catholic, this gang did not join in with members of the Klu Klux Klan

instead they organized their own violent attacks. Ragen’s

Colts described themselves as an “athletic” club but they

actually were the

Irish Mafia which engaged in

violent, criminal activities.

According

to the grand jury, members

of Ragen's

Colts disguised themselves

in blackface and set

fire to homes in the

Lithuanian and

Polish immigrant

neighborhoods. Fortunately,

Marek’s home was not burned but

Polish immigrant homes near

the Stockyards were.

Why would the

Irish set fire to fellow,

mostly Catholic, immigrants’

homes? Their hope was to draw the Polish

immigrants into their

bloody attacks against

African Americans.

Ragen’s Colts committed arson in an attempt to overcome the lack

of interest in rioting among Polish immigrants and force them

to participate in the brutalization of African Americans. The Irish

knew they had many interests in common with Polish

immigrants. Both groups were mostly Catholic, lived in substandard

housing and earned low wages in dangerous jobs.

Yet, in one of the most bizarre examples of racial intolerance,

the Irish gangs chose to use arson and then blame African Americans in an

attempt to create unity among the European

immigrants as Whites.

But, even after Ragen's Colts' blackface arson attacks, Polish immigrants did NOT join in rioting with the Irish. Why not?

|

Premier scholarship on the Polish in Chicago.

|

Unlike the Irish, Polish immigrants, like Marek, didn’t

identify nor act as Whites.

Many Poles believed that the riot was a conflict between two groups

of people with Poles abstaining because they belonged to

neither group. They were Polski

-Polish.

The Poles worked

in factories and stockyards with immigrants from all over the world

as well as African Americans, but they lived in communities that were

reincarnations of their villages in Poland. In fact, for his

entire life in Chicago, Marek never left a 10 block area.

Everything his family needed - work, church, school

and shopping - was in his Polish community - Kazimierzowo.

|

| Polish Community in Chicago |

This view is not surprising due to the poor conditions in Poland from which they fled. Again, they were already familiar with pogroms and maintained their Polish wariness of any type of pogrom.

It wasn’t until the 1930s that they transitioned from Polski to Polish Americans.

Even Marek’s granddaughter, my mother, maintained her Polish identity throughout her life and had a great interest in political events in Poland. THE $10,000 question: Did

Marek participate in the

riots? While

it is historically

and geographically

possible that

Marek

could have

participated in

the

violent and random attacks of African Americans during

the 1919 Chicago Race Riots,

however,

based upon my

research, I think it is

extremely

unlikely that he did.

He

had no NEED

to assert himself through violence. Marek

may (or

may not)

have

been one of those immigrants

who

was outraged about

African American migrants from the south.

But, he needed to

support his wife and 5 children. Marek needed his job, more than anything. Engaging

in violence would not

meet his need for employment. In fact, violence was not going to be

of any help. Beating

people and destroying property is not only wrong, it would do nothing

to better his family’s situation. Marek (and everyone else!) would

gain nothing

by engaging in violence. I

think it

is highly unlikely he would

have

felt

the need to participate

in the riots.

Secondly,

Marek did not share the

NARRATIVE

of the rioters. He experienced

antisemitism and pogroms in Poland

which were fueled by fear and hatred. The

narrative Polish immigrants were familiar with was the

pogrom violence in Poland's

Galicia province. Tens of thousands of Jews were killed between 1918 and

1920. The

race riots looked just like those pogroms, only the targets in the United States were African Americans.

Polish immigrants viewed African Americans as unfortunate victims of hate. Marek's,

and other Polish immigrants' narrative was to avoid pogroms/race riots either as a target or as a participant.

Finally,

Marek did not share a NETWORK

with the rioters. Ragen’s Colts were a “network,” a gang that shared a need – to assert power - and a narrative –

“whites are better than blacks” - which led them to commit

violence. It is documented

that Polish immigrants choose

NOT to

participate in the rioting

even after Polish

homes were destroyed by

Ragen’s Colts.

Polish immigrants in 1919

identified as Polski

not as “white.”

Marek was

Polski.

Marek’s

network was his family, work, and the Polski community.

In conclusion, there

really is no logical reason why Marek

would

have participated in the 1919 Chicago Race Riots. He

had no need, narrative nor network that would have motivated him to

participate.

WHY DO RACE RIOTS HAPPEN?

After the race riots, people

tried to make sense of what happened and why.

A

commission, established by the Governor

of Illinois,

released a report three years after

the riots: The

Negro In Chicago: A Study on Race Relations and a Race Riot.

The commission members, six black men, six white men, looked at the

root causes behind the riot and concluded, as would the Kerner Commission Report 50 years later, that racial inequality was a

major reason for the violence. Unfortunately, whether because of racism or fear, government

and business leaders choose segregation to address the racial

inequality identified by the commission. That is the choice that we

have dealt with and continue to deal with today.

The legacy of the 1919 Chicago Race Riot left physical scars on the

city and its citizens. The city became officially segregated. Six

years after the riots, housing was “red lined” and restrictive

covenants created residential segregation.

Then 40 years later Interstate highways were built through Black

neighborhoods, destroying them. This happened in cities all across

our nation, including Jacksonville.

What was the aftermath like for Marek and his family? Sadly, Marek would be dead within 2 years of the race riots. Immediately after the riots, Marek continued to work as a molder at International Harvester. In 1920, Marek and Anna welcomed their 6th child, a daughter. The next year, at age 40, Marek died from pulmonary Tuberculosis. His wife, Anna, was left a widow with 6 children. She then married a fellow Polski from Galicia, Josef Persak, and they had a daughter. In 1930, there were 10 people, including my newlywed grandparents, living in Anna’s flat in the same neighborhood - Kazimierzowo. In 1941, Marek’s wife, Anna, died at age 56 from untreated high blood pressure.

|

My Grandparents: Ruth and Joseph Niemiec - Marek and Anna's son.

|

Marek’s son, Joseph, attended school through the 8th Grade and then began working in the Stockyards. Eventually, Joseph became a foreman in a glue factory. Since Joseph was considered “white,” he was able to move to Austin, a middle-class neighborhood on the west side of Chicago and purchase a detached, single-family home.

|

Marek's Granddaughter, Naomi - my mother.

|

There his daughter, Naomi - my mother, was raised in a 99.9% White neighborhood. She eventually married and moved across the state to Moline, Illinois.

|

Aftermath of 1968 Chicago Riots

|

Almost 50 years after the 1919 Race Riots, Marek’s granddaughter would return to his neighborhood. It was after the 1968 Chicago Riots, when Naomi and her cousin drove across the state to attend their grandmother's funeral in Chicago. I remember my mother telling me about their experience driving through Marek’s devastated neighborhood. She described people looking directly into the car at her and her cousin as they drove down the streets, “There was hate in their eyes. My cousin was afraid but I understood why they looked at us like that. They did not see me, a working mother of six, on her way to her grandmother’s funeral. They only saw me as a “white.” I felt very sad.”

I am

sure the last thing Marek expected to experience in the United States

were pogroms but he did. We

think these things can't happen again

- especially in the United States!

We think of the past as

gone or

being somewhere else,

but at this moment in

this place, the race

riots are with us still. We're still struggling with how to get along

with each other. And,

just like Marek, we have

the freedom to choose what sort of person we will be in any given moment.

In every

situation we have a choice. Even

amid dark, dangerous events, how

we choose to react to the situation is totally up to us. It

is important

to learn why

and how, not

just our ancestors, but all people

acted during times of crisis.

This knowledge,

in turn, can help us to

respond to whatever events we experience.

Learning our history, recording it, and preserving it benefits

not only our related family, but the entire human family. It

is the story of who we are, where we come from, and can potentially

reveal where we are headed.